All Currencies Devalue or Die

On long-term debt cycles in Ray Dalio’s “The Changing World Order”

“All currencies devalue or die,” writes Ray Dalio in The Changing World Order. “Of the roughly 750 currencies that have existed since 1700, only about 20 percent remain, and all of them have been devalued.”

Prosperous states (as well as those that are no longer prosperous but still think that they are) have an inherent tendency to overextend and overspend, resulting in an insidious buildup of debt that becomes ever more difficult to repay. These states then begin printing money to keep paying the bills, gradually destroying the value of their currency in the process. This tendency is a natural law of misgovernment, and although it may be curbed by individual leaders, over time it always prevails. The question isn’t whether or not a currency will be devalued or die, but how soon it will happen.

There is a belief in sailors’ lore that waves come in sets of nine, with the ninth being the biggest and deadliest. This is a bit how capital and debt cycles work. Dalio explains that the short-term boom and bust cycles we experience every few years are themselves a part of a larger capital and debt cycle, which lasts (very roughly) 75 years. Unlike the waves in sailors’ lore, however, what grows with every short-term cycle is not its magnitude but the country’s debt burden. The ship’s hull gets weaker and weaker with every wave, and, when another one inevitably arrives, it is unable to withstand the crash. The collapse always comes as a surprise because it happens once in a lifetime, so by the time it takes place, the last one has already been forgotten.

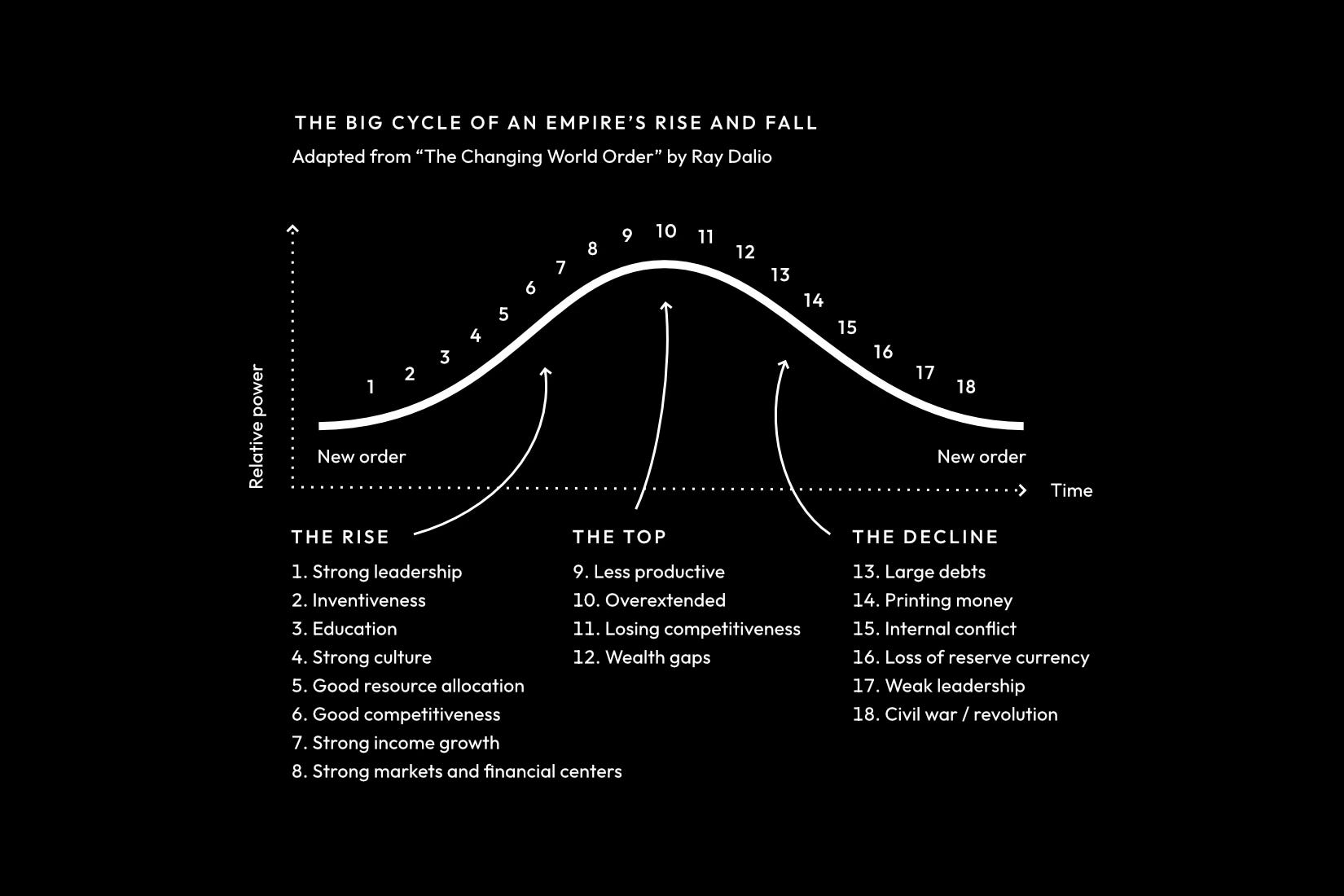

The timing of the ninth wave matters. The focus of Dalio’s book is a study of what he calls the “Big Cycle” that covers the rise and fall of every empire. This cycle interacts with and is influenced by three other cycles. One is the capital and debt cycle mentioned above. The other two are internal and external order and disorder cycles. These reflect the political situation within a country, and the political situation in the world at large. As the names suggest, these cycles revolve around states of order, unity and peace, and chaos, discord and war. The cycles follow their own timelines, but sometimes they align, and when they do, “the tectonic plates of history shift.” Depending on the stage in the cycles, this either results in a period of tremendous prosperity, or it results in collapse, revolution and a new world order.

As the world’s leading empire, the United States enjoys the “exorbitant privilege” of owning the world’s main reserve currency, the US dollar, which other countries use for international trade and as a store of value. Being the owner of a reserve currency is nice, but being the owner of a fiat reserve currency is a bit like having your own magic money tree. Unlike hard money (e.g. metal coins), or banknotes that are backed by hard money, the supply of fiat money can be increased indefinitely.1 You can print it. And because you can print it, you can print your debts away.2 Normally this wouldn’t work because it would cause hyperinflation (e.g. the Weimar Republic hyperinflation of 1921–1923, which I wrote about previously). The case of the United States differs in that, being the world’s main reserve currency and instrument of trade, countries can’t just dump the dollar tomorrow and go elsewhere. With no good alternative, they are forced to absorb the loss of value caused by the US printing machine. But they won’t keep absorbing it forever.

There are only four ways of reducing debt: spend less, raise taxes, print money, or just don’t pay it (i.e. restructure debt or default on it). The last option is saved for last, because once it’s used, no one will lend you money. The first two are very costly politically. No politician wants to be the one to cut government services or raise taxes. The cost to the public from printing money is the same as raising taxes, but, because it happens through inflation, the cause and effect relationship is obscured—i.e. it will be the businesses who will raise prices, and not the government who will raise taxes. Consequently, if the option to print money is available, governments will almost always take it.

Printing money doesn’t necessarily depreciate the currency. If an economy produces more value in tangible goods than the amount of money printed, then the currency will keep its worth, or even appreciate. Conversely, if the economy is unproductive, the added money supply will dilute the value of the currency. This is the crux of the issue. Once you print the money, you can spend it in two ways. You can spend it on things that increase productivity (e.g. infrastructure and education), or on things that don’t (e.g. welfare). The former increases a country’s output and strengthens its currency. The latter depreciates the currency, which simultaneously makes it a bad store of value, because the currency is now worth less, and discourages lenders, because the value they get in return shrinks. The point isn’t that you shouldn’t spend money on the latter, only that this cannot be done using unearned money without depreciating your currency.

On the other hand, money spent on things like infrastructure and education, even if it’s been printed, turns into real assets that will continue to generate returns, no matter what happens to the currency. The Singapore miracle, for example, was ignited by heavy investment in industrial infrastructure (i.e. whole industrial parks were built for companies to just move in). This attracted a flurry of overseas businesses to set up their production there, long before they even considered going to places like China. Moreover, Lee Kuan Yew was explicit about keeping the money supply in check. “I had decided in 1965, soon after independence, that Singapore should not have a central bank that could issue currency and create money. We were determined not to allow our currency to lose its value,” writes Lee Kuan Yew in From Third World to First. The Monetary Authority of Singapore would “have all the powers of a central bank except the authority to issue currency notes.” Today, on a per capita basis, Singapore is wealthier than the United States.

The problem, however, is that the policies that promote long term goals are not going to be very popular when they require short term sacrifices. “Reversing a decline is very difficult because it requires undoing so many things that have already been done,” writes Dalio. “For example, if one’s spending is greater than one’s earnings and one’s liabilities are greater than one’s assets, those circumstances can only be reversed by working harder or consuming less.” Once people are used to a certain standard of living, they’ll expect it to continue, even if the economy cannot sustain it, compelling the government to keep spending in order to maintain the illusion of prosperity that no longer exists. But the illusion can only be maintained for so long. Eventually, the “Unveracity is worn out,” as one author put it, and you are left desolate.3

Fiat money is itself the final stage of the cycle of money types. All states first begin with hard money, then switch to banknotes backed by hard money when they need to expand credit, and then finally abandon hard money altogether for fiat money in order to take full control over its supply. Irresponsible printing eventually wipes out the value of the currency and forces people to switch back to hard money, restarting the cycle. Actually, it’s possible to increase the supply of hard money as well. The Romans started debasing their silver coinage from the time of Emperor Nero by mixing silver with base metals. This continued with every new emperor, until the coins had almost no silver left in them at all.

It’s a little more complicated than this, of course. The money isn’t actually printed (it’s done via digital ledger entries), and it isn’t used to pay back the debts directly, but the result is the same.

From Thomas Carlyle’s Past and Present, in which he essentially predicts the revolutions and the rise of communism and fascism of the 20th century (which would, in his view, result from a combination of the ineptitude of the ruling elites, who have become incapable of ruling, and the narrow selfishness of the capitalists, who are capable of ruling but do so only for their own private interest). In one part of the book he explores the history of the Abbey of St Edmunds, chronicled by one of its monks in the 13th century. The monk recounts how the abbey had over the years accumulated massive debts. The abbot didn’t try to fix it. He simply to ignored the debts, and kept borrowing even more money at crippling interest to keep paying the bills. He even gave out special seals that permitted other monks to take out loans in the abbey’s account. When the old abbot died, however, his replacement took on his new job with exceptional seriousness and zeal. He immediately ended the taking out of new loans by seizing the seals from other monks and breaking them. He cut spending and worked on boosting the abbey’s income. The monks grumbled and resisted, but the finances soon improved and, in time, the debts were all paid off.