Evil Is Nothing

A philosopher sentenced to a gruesome death wrestles with the nature of good and evil. On Boethius’ “Consolation of Philosophy.”

“Please stop representing yourself as a philosopher, you affected fool!” cried Epictetus in one of his lectures. “You still experience envy, pity, jealousy and fear, and hardly a day passes that you don’t whine to the gods about your life. Some philosopher!”1 The Stoic sage is talking about scholars who know a great deal of theory but apply nothing in practice, who can talk for hours but are completely powerless in the face of adversity.

When, sometime in AD 523, the Roman philosopher Anicius Boethius was imprisoned and sentenced to death (including a bout of gruesome torture), the question of the value of his learning was put to him in no uncertain terms. Having lost his considerable power and wealth, he found himself in the position of those so-called philosophers Epictetus was criticizing. As he sat in prison awaiting execution, he began writing, structuring his thoughts as a conversation between himself and Philosophy, who materializes in his room to help him confront his predicament. The result is the most widely read philosophical work of the Middle Ages: On the Consolation of Philosophy.

“This, then, is how you reward your followers,”2 Boethius complains bitterly to Philosophy. He followed her guidance by spoking the truth, only to find himself punished like a criminal, with suffering and death as his reward. And the real criminals? They are the ones doing the sentencing, the ones left to enjoy their plunder. How could this in any way be just, and how could he be expected to do anything other than despair at his unhappy fate?

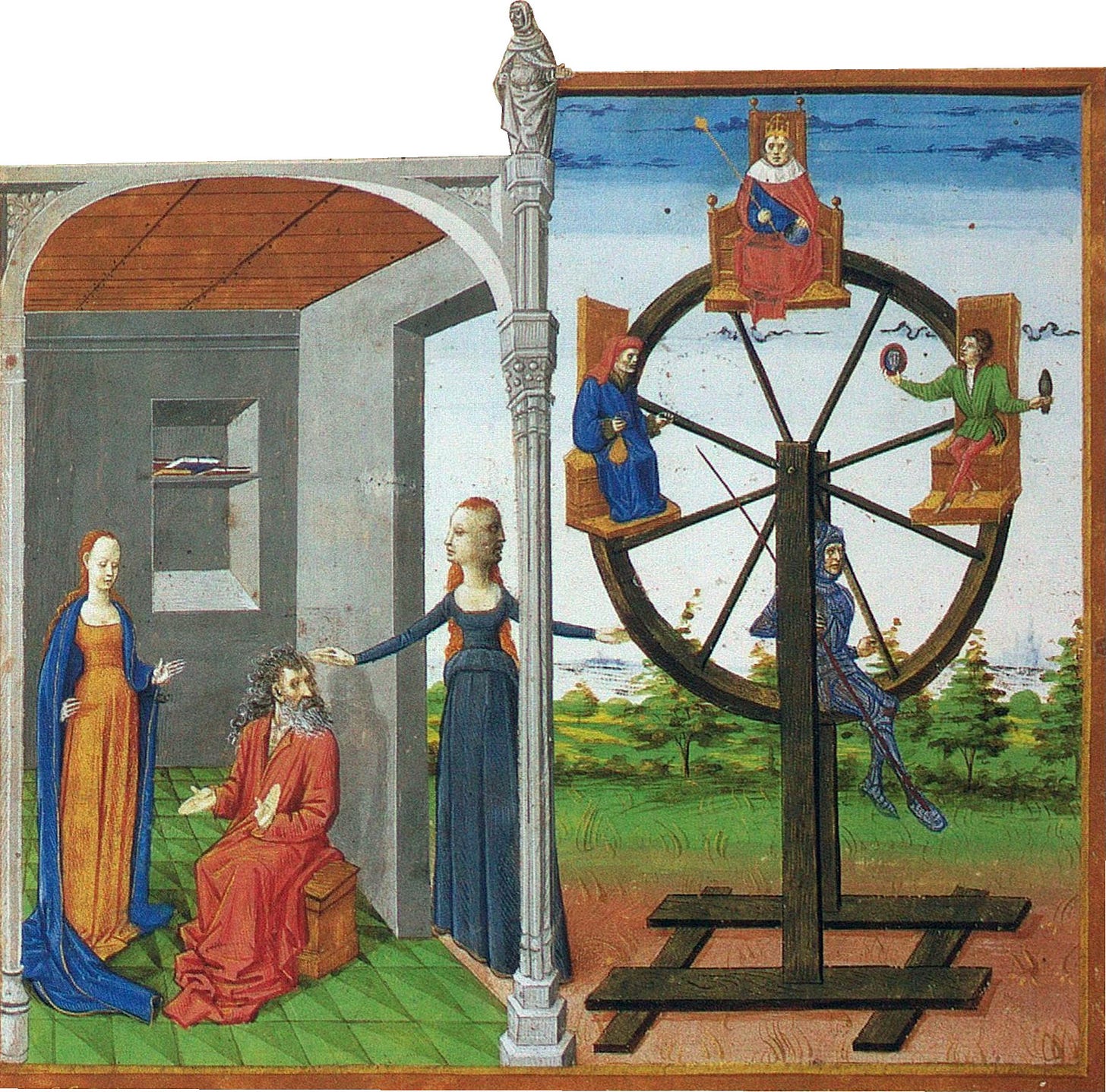

Boethius’ Philosophy begins by explaining that the things he is distressed about losing are not only worthless, but never even belonged to him in the first place. She does this by painting a picture of Fortune and her wheel, the Rota Fortunae, upon which she keeps spinning human fates. On one side of the wheel are those moving up in life, on the other going down. Some get a lucky break and are propelled on their way to wealth, power and fame. Others suffer misfortunes and lose everything they’ve gained. The point is that Fortune is always spinning her wheel, and those who are enjoying prosperity now are certain to experience setbacks or even disasters in the future. “Change is her normal behavior, her true nature. In the very act of changing she has preserved her own particular kind of constancy towards you.” Building your happiness upon the things that don’t really belong to you but to Fortune, and which she is going to take away tomorrow, is a sure path to misery.

Moreover, getting more from Fortune isn’t even a good thing. For example, the wealthier you become, the more anxiety you will feel about losing it all. “How splendid, then, the blessing of mortal riches is! Once won, they never leave you carefree again,” mocks Philosophy. Power is no better, for not only does your position grow more dangerous the higher you rise, but the people who try to befriend you do so for their own selfish ends, ready to betray you the moment Fortune turns against you. Even kings have the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads—especially kings. “What sort of power is it, then, that strikes fear into those who possess it, confers no safety on you if you want it, and which cannot be avoided when you want to renounce it?” Fame, even if it is deserved, doesn’t last, and the pursuit of bodily pleasure, taken beyond moderation, results in illness and pain.

And yet, we cannot say that wealth, power, fame and pleasure are bad and undesirable. There is something about each of them that is clearly good. It is good to be self-sufficient, good to be strong, good to be honored and respected, and good to be joyful. Those who pursue these things are therefore not wholly wrong. The problem, explains Boethius’ Philosophy, lies in division. What people typically do is pursue one of these goods at the expense of the others. This makes them unhappy because they are always lacking something in their lives:

If a man pursues wealth by trying to avoid poverty, he is not working to get power; he prefers being unknown and unrecognized, and even denies himself many natural pleasures to avoid losing the money he has got. But certainly no sufficiency is achieved this way, since he is lacking in power and vexed by trouble; he is of no account because of his low esteem, and is buried in obscurity. And if a man pursues only power, he expends wealth, despises pleasures and honor without power, and holds glory of no account. But you can see how much this man also lacks; at any one time he lacks the necessaries of life and is consumed by worry, from which he cannot free himself, so he ceases to be what he most of all wants to be, that is, powerful. A similar argument can be applied to honor, glory, and pleasures, for, since any one of them is the same as the others, a man who pursues one of them to the exclusion of the others cannot even acquire the one he wants.

Boethius’ Philosophy explains that if you want to be happy, you must pursue all facets of happiness at once, or rather, you must pursue that which is the source of all the goods and therefore the source of perfect happiness. Because the unity of all the goods is the highest good the human mind can conceive, Boethius identifies it with God. To pursue God means to pursue perfect goodness, i.e. to pursue all the things that constitute the good life simultaneously: self-sufficiency, strength, honor, glory and joy. Put another way, the path to happiness is virtue.

Boethius essentially makes the same conclusion as the Stoics, although he arrives there via a different route. The Stoic argument is, briefly, as follows: there are things that are under our control (our impressions and will), and others outside our control (all externals). Focusing on things outside of our control makes us unhappy because even though we can influence them, we cannot guarantee their results. Even if you do everything right, events wholly outside of your power—wars, natural disasters, diseases—can prevent you from achieving your goals. So rather than focusing on outcomes, focus instead on how you deal with whatever Fortune throws your way, both good and bad. The Stoics don’t assign value to outside events—nothing external is good or bad, it’s all indifferent. What is good or bad is how you act. Do you give in to base instincts like fear, anger, impatience and greed, or do you behave courageously in the face of misfortune, and with self-restraint when things go your way? A good life is a virtuous life, not a fortunate one.

Boethius’ imprisonment is therefore not a misfortune at all but an occasion to show his virtue. “A wise man ought no more to take it ill when he clashes with fortune than a brave man ought to be upset by the sound of battle,” writes Boethius. “For both of them their very distress is an opportunity, for one to gain glory and the other to strengthen his wisdom.” In fact, there would be no such thing as virtue if there was no adversity to overcome. Moreover, we wouldn’t even know Boethius’ name today had his life been spared.

For Epictetus, this perspective meant ultimate freedom. Because everything that happens to you is an opportunity to build and display virtue—the four Stoic virtues being courage, temperance, justice and wisdom—nothing can stop you from living the good life, no matter how short or long it may be. Your actions always achieve their ends because the ends lie in the actions themselves, not in external goals. And, unlike the worldly goods of wealth, power and fame, nothing can take your goodness away from you.

Epictetus goes as far as to define a Stoic “simply as someone set on becoming a god rather than a man.” Boethius actually makes the same assertion, saying that the “reward of the good … a reward that can never be decreased, that no one’s power can diminish, and no one’s wickedness darken, is to become gods.” Boethius explains it in terms of possessing goodness and happiness, both of which he identifies with divinity. For Boethius, those who lead good lives are happier, and consequently more divine. “While only God is so by nature, as many as you like may become so by participation.”

But the reverse isn’t true—that is, evil men don’t become devils. Evil men forfeit their very existence, they cease being human. Boethius arrives at this conclusion by following his solution to the problem of evil. If an omnipotent God can do everything, then he can also do evil, but if he can do evil, how can he remain perfectly good? The answer is that Boethius’ omnipotent God cannot do evil. Why not? Because “evil is nothing.”

This is quite an assertion, but it’s not a new one. Writing over a hundred years earlier, Augustine explained it in his Confessions in terms of corruption. If we imagine a scale from something that is supremely good, which is therefore incorruptible, and wholly corrupted, which therefore has nothing left to corrupt, then corruption—that is, evil—is not a substance, but a deprivation of the good. Though not the same, this position is also not a radical departure from the Stoics, who don’t assign value judgements to the external world. Nothing in the world is good or bad, it just is. For the Stoics, the idea of good and evil applies solely to our actions (and even there, evil is seen more as a defect—a moral blindness). Because being imprisoned, stripped of his wealth and sentenced to death does not diminish Boethius’ goodness, it therefore does him no harm.

Boethius views people’s actions from the perspective of their relationship to God, which he identifies with supreme goodness—the “common goal of all things that exist.” From that perspective, bad actions are not really evil, they are futile, that is, they completely miss their mark. An evil man cannot harm others because he cannot take away their goodness, he can only harm himself by diminishing his own. “Evil is not so much an infliction as a deep set infection.”

Although Boethius does not use the following analogy, I think the concept of order and chaos also works to explain his interpretation of evil. If we imagine that everything is part of a divine order (“all that exists is in a state of unity and … goodness itself is unity”), then everything that detaches itself from this order disintegrates into chaos (“everything which turns away from goodness ceases to exist”). The material remains, but any higher forms composed of that material perish. By committing evil deeds, people harm themselves by disintegrating that which makes them human: their goodness. They don’t disappear, but they debase themselves to the level of animals:

You could say that someone who robs with violence and burns with greed is like a wolf. A wild and restless man who is for ever exercising his tongue in lawsuits could be compared to a dog yapping. A man whose habit is to lie hidden in an ambush and steal by trapping people would be likened to a fox. A man of quick temper has only to roar to gain the reputation of a lion-heart. The timid coward who is terrified when there is nothing to fear is thought to be like the hind. The man who is lazy, dull and stupid, lives an ass’s life. A man of whimsy and fickleness who is for ever changing his interests is just like a bird. And a man wallowing in foul and impure lusts is occupied by the filthy pleasures of a sow. So what happens is that when a man abandons goodness and ceases to be human, being unable to rise to a divine condition, he sinks to the level of being an animal.

Near the end of his Consolation, Boethius uses an image similar to the wheel of Fortune to illustrate the relationship between God’s plan (Providence) and its realization in the world (Fate). Imagine a series of revolving, concentric circles. As you move further away from the center, a point on a circle travels ever greater distances as it spins around. As you move closer to the center, the distances decrease. The point at the very axis doesn’t move at all—it is Providence.3 Thus, “whatever moves any distance from the primary intelligence becomes enmeshed in ever stronger chains of Fate, and everything is the freer from Fate the closer it seeks the center of things. And if it cleaves to the steadfast mind of God it is free from movement and so escapes the necessity imposed by Fate.”4

The human being is like vessel filled with a part of the divine, with goodness, which he can choose to increase by pursuing the good life, moving away from the maelstrom of fate towards the still point in the center—himself becoming divine “by participation”—or diminish by acting otherwise and “cease to be at all,” letting his body be whirled round by fate. On the one extreme, the vessel ultimately discards its shell and becomes its contents, on the other, it empties its contents and becomes its shell. Boethius chose the former and, despite the destruction of his vessel, his soul lived on in the form a thread woven into the fabric of civilization. His oppressors chose the latter and were erased from collective consciousness.

Discourses by Epictetus, Robert Dobbin translation (Penguin, 2008). The Stoics included pity in the list of negative emotions, which makes sense from the perspective of things that make you abandon reason. This doesn’t imply a lack of compassion. In other places, for example, Epictetus tells his students to be compassionate to others, in particular those who suffer as a result of not knowing how to lead good lives.

All quotes by Boethius are from the Victor Watts translation of the Consolation of Philosophy (Penguin, 1999).

As I mentioned in my post on thinking, medieval mystics used the Latin term nunc stans—the “standing now”—to describe eternity as an attribute of God. The stillness of meditation could be seen as a kind of bridge to eternity.

This is strikingly similar to what is written in the ancient Hindu scripture, The Bhagavad Gita: “The spirit of man when in nature feels the ever-changing conditions of of nature. When he binds himself to things ever-changing, a good or evil fate whirls him round through life-in-death. But the Spirit Supreme in man is beyond fate … He who knows in truth this Spirit and knows nature with its changing conditions, wherever this man may be he is no more whirled round by fate.” (Chapter 13, Juan Mascaró translation).