It Was Probably the Name of a Deity

Justin Kaplan's "When the Astors Owned New York" tells the story of a family feud that fueled the creation of New York's most famous grand hotels.

Nothing ennobles a human being like work. Without work, a human being cannot maintain his human dignity. This is why idle people care so much about superficial grandeur: they know that without it they would be despised.

—Leo Tolstoy, The Circle of Reading (19 February)

In 1834, a wealthy tycoon bought up a whole block of houses in the center of New York. He wanted to demolish them to make space for his life’s crowning monument, his palais royal. There was just one hiccup. One of the residents was not willing to sell. After protracted haggling, the owner finally agreed to several times the market value. But when the workers arrived to begin demolishing the house, they discovered that the owner was still inside. “Well, never mind,” the tycoon told them, “just start by tearing down the house anyhow. You might begin by taking away the steps.”

The tycoon was John Jacob Astor, the founder of one of New York’s wealthiest real estate dynasties, whose story Justin Kaplan tells in When the Astors Owned New York. Besides the the rags to riches tale of the dynasty’s founder, the book focuses on the story of his great-grandchildren, whose limitless wealth, coupled with a deep need to prove themselves worthy of it, resulted in their pursuit of a particular form of conspicuous consumption: the building of grand hotels.

John Jacob Astor was born in 1763, in a German village called Waldorf. He emigrated to the United States when he was still young, coming to New York via London, and began working for a Quaker named Bowne, scraping, cleaning and curing undressed pelts into furs. When he had gathered enough money and experience he set off on his own, and, after fifteen years in the fur business, managed to amass a small fortune.

But the insatiable Astor was not the type of man to find satisfaction in the comforts and safety of a relatively well-to-do life. He wanted much more. His ambition was not limited to New York, or even to America—it was global. He threw all his energies into a new project, which he called the Pacific Fur Company. His idea was to build on the success of his fur business in New York by establishing an international trading triangle. He would acquire a fleet of ships to take his furs all the way to Shanghai, where they would be traded for such things as tea, spices and silks. These would then be taken to Liverpool and traded for British manufactures, which in turn would be taken back to New York. As the project went underway Astor could vividly imagine the prosperous future of his new global commercial empire.

Alas, the project was a complete failure. Astor blamed it on “blundering subordinates, Indian treachery, the War of 1812, bad weather, and just plain bad luck.” But the way he reacted to his shattered dreams reveals the reason he was in a position to embark on such dreams in the first place. Asked about the disastrous end of the enterprise, Astor replied: “What would you have me do? Would you have me stay at home and weep for what I cannot help?” What made Astor so successful was not just his insatiable appetite for acquisition and wealth, but the stoic way in which he accepted setbacks. Instead of wasting his energies and draining his motivation by feeling sorry for himself, Astor simply found something else to work on.

And what he did next turned out to be as successful as his previous project had been a failure. Astor used the profits from his fur business to begin buying up real estate around New York, particularly in Manhattan. This happened to be the ideal time and place to go into real estate. In the seven decades from 1780 to 1848, the year Astor died, the population of Manhattan grew from 25,000 to about 500,000. Astor’s insatiable greed dictated his strategy to buy and hold, with no intention of selling. His Manhattan properties continued to accumulate and accumulate and, as the city expanded and thrived, the value of his portfolio exploded. As the biographer James Patton wrote, “the roll-book of his possessions was his Bible. He scanned it fondly, and saw with quiet but deep delight the catalogue of his property lengthening from month to month. The love of accumulation grew with his years until it ruled him like a tyrant.” The fortune he accumulated was so great that half a century after his death a Chicago lawyer spread rumors that Astor had actually obtained his wealth not through his businesses, but by getting his hands on the hidden treasure of the infamous British pirate Captain William Kidd.

Near the end of his life, John Jacob Astor started thinking about his legacy. He wanted to transform his wealth into a visible monument to his success. It was then, in 1834, that he decided to build a grand hotel. At the beginning of the 19th century, luxury hotels were something very new. As Kaplan writes, “American hotels of the time had barely evolved from roadside inns and taverns in nondescript houses. Their patrons, mainly commercial travelers, had few expectations beyond basic food, drink, and shelter and a bed for the night, preferably one not shared with strangers.” The grand hotel would transform what was heretofore a utilitarian service—a place for travelers to safely spend the night—into a destination in itself, a place that offered both an opportunity to enjoy worldly pleasures and an occasion to flaunt one’s wealth. The hotel would become a status symbol. Two years later, in May 1836, Astor House opened its doors.

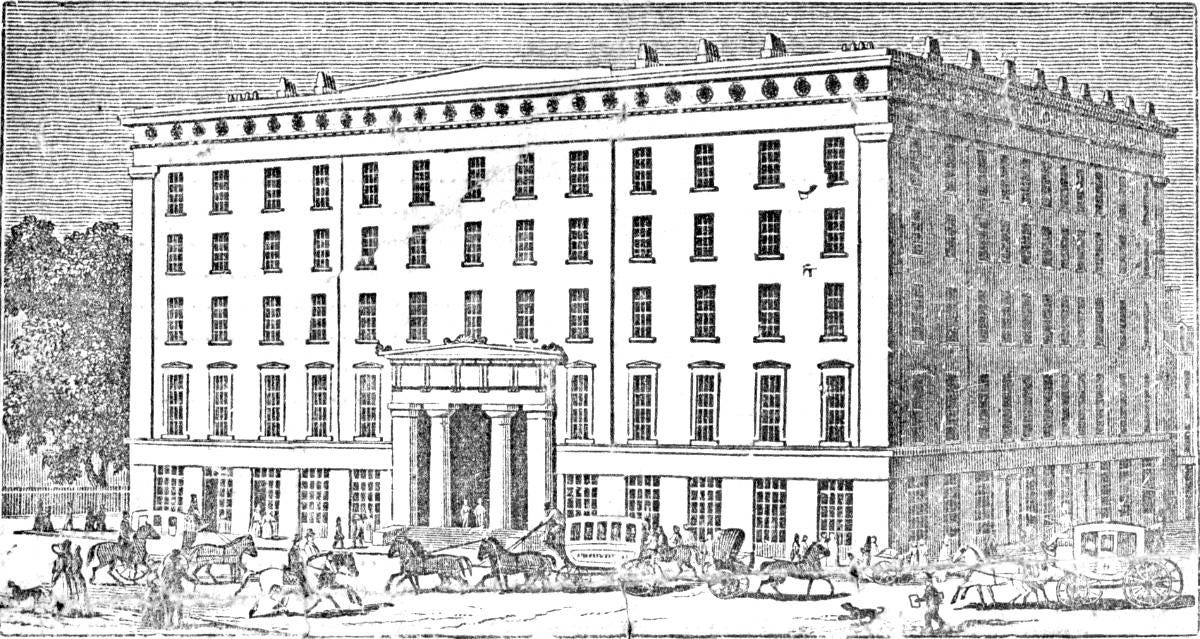

Six stories high, with a Greek Revival granite portico opening onto Broadway, Astor’s hotel employed a staff of over a hundred and contained three hundred guest rooms richly furnished with custom-made sofas, bureaus, tables, and chairs of expensive black walnut. A steam engine in the basement pumped water to the upper floors from artesian wells and from two forty-thousand-gallon rainwater cisterns. Anticipating the boutique-ing and malling of the modern big-city hotel, the ground floor housed eighteen shops and served as a marketplace for clothing, wigs, clocks, hats, jewelry, dry goods, soda water, medicines, books, cutlery, trusses, pianos, and the services of barbers, tailors, dressmakers, and wig makers. Lighted with gas from the hotel’s own plant, the lobby, public rooms, and corridors, carpeted and furnished with satin couches, became a social focus, a public stage for the display of celebrity and fashion. An immense dining room, with its silver and china alone costing about $20,000, served meals at any time of day or night, a departure from the standard boardinghouse and hotel practice of fixed sittings.

By building his grand hotel, Astor had discovered a way to convert his money into status. He transformed his wealth into a monument under whose roof the greats of the nation—and even the world—would assemble, and above whose entrance his name would be carved. He had built a palace for the age of commerce and industry, a palace to which admission could be bought, and the buying of which in effect boosted the prestige of both, those who would flaunt their wealth by staying at such a place, and the one who had built it.

Soon, all the important people of the day would make their way through the doors of Astor House whenever they were in New York. Nothing less would do. In time the guest list would include “Andrew Jackson, Sam Houston, Henry Clay, and Stephen Douglas; Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray; the French tragic actress Rachel; former president of the Confederate States Jefferson Davis, … Grand Duke Alexis of Russia … and the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, the first British royalty to visit New York.” As one editor told his staff, whom he sent to keep track of the hotel’s arrivals, “Anyone who can pay two dollars a day for a room must be important.”

John Jacob had two sons, William Backhouse and John Jacob II. The latter was “mentally incompetent” and had no future role in the dynasty. The former, “phlegmatic and cautious,” continued the work of his father, protecting and growing the family fortune, which he passed on to his three sons. The next generation could not have been more different in character. Henry completely abandoned the business and went off to marry a farmer’s daughter. The “imperious and somber” John Jacob III balanced “thrift, work, piety, and high morality” with “his class’s conventional pleasures: vintage claret, fine book bindings, and a villa on Bellevue Avenue in Newport.” His younger brother, William Backhouse Jr., pursued a life of unrestrained pleasure, spending his time on “yachting, womanizing, low company, Thoroughbred horses and bloodhounds, sullenness, and drink.” As one contemporary quipped, he was “a one-man temperance society, dedicated to destroying all spirituous liquor even if he had to drink it all himself.”

The two brothers did not get along, and they passed their differences down to the their two sons, each of whom seems to have been moulded in the image of their respective father. William Waldorf, the son of John Jacob III, was a somber, serious, scholarly romantic who pursued a blue-blood image of a cultured gentleman. His interests in art and literature led to his buying the Pall Mall Magazine and the Pall Mall Gazette in London and even recreating a complete Roman villa in Italy atop its ruins, fully furnished with as many antiques of the period he could get his hands on. The relationship between him and his cousin’s family was never great, but the rift really deepened when his aunt changed her calling card from “Mrs. William Astor,” to “Mrs. Astor,” thereby seizing the title from William’s own wife, who did not have the energy or the will to fight the gregarious “Mrs. Astor.” William then decided to move to London, but rather than go quietly, he saw fit to announce to his countrymen that “America is not a fit place for a gentleman to live … America is good enough for any man who has to make a livelihood, though why traveled people of independent means should remain there more than a week is not readily to be comprehended.” His countrymen did not appear to share the same sentiment, and the press fired back with a vengeance, reminding him of his family’s humble origins and dubbing the Astor emigre “William the Traitor.” His effigy was said to have been burned on the streets of New York.

William Backhouse Jr.’s son John Jacob IV, did not fare any better in the eyes of the public. A “chronically humorless” man, Jack was avid inventor, creating such things as improved bicycle breaks and suction systems for deck chairs to keep them from sliding. Some of his creations gained some renown, for example, his “pneumatic road-improver,” which “blasted away dust and dried horse manure from paved surfaces,” won a prize at the Chicago Exposition in 1893. He loved cars, collecting dozens of them at his mansion at Ferncliff, and also authored sci-fi novels, daydreaming about the workings of the city of the future. Alas, like his cousin William, Jack’s reputation also took a fall. Just as he had entered society, an incident took place at a restaurant. An argument over who got to sit next to an upper-class beauty flared up in the restaurant’s restroom, developing quickly into a full-on brawl, with Jack and his adversary attacking each other with both their fists and canes. The press, filled with mirth and mockery, called the young Astor “Jack Ass,” a nickname that would linger right until his untimely death aboard the Titanic.

“A wealthy man,” Tocqueville had written in the 1830s, “would think himself in bad repute if he employed his life solely in living. It is for the purpose of escaping this obligation to work that so many rich Americans come to Europe, where they find some scattered remains of aristocratic society, among whom idleness is still held in honor.” In a society that, unlike Europe, had no tolerance for “idleness” and no commonly accepted concept of leisure (“the nonproductive consumption of time,” in Thorstein Veblen’s definition), wealth alone could condemn its possessors to dwindle into playboys, “clubmen,” sportsmen, alcoholics, expatriates, and eccentrics who pursued amusement and novelty to allay their boredom, lassitude, and inertia.

As much as it was a blessing, the cousins’ wealth did little to help them earn respect in the eyes of the American public. But one idea stood out to them. Their desire to prove themselves worthy of their wealth, combined with their personal dislike of one another, spurred them to pursue the path began by their great-grandfather. They would build great monuments to themselves in the form of grand hotels. The first shot was fired by William when he demolished his father’s brownstone mansion on Fifth Avenue to build the Waldorf, the most luxurious hotel in the country. As Kaplan puts it, it was “an expatriate’s declaration of personal magnificence, blue-blood pride and superiority in imagination, style, and intellect to the members of his class and the nation at large.” William “kept an eye on the layout and decoration of his hotel, stipulating, for example, hand-painted decorative ceilings in each room, bathrooms that opened out on a wide court, and such imported innovations as a concierge to preside over the hotel entrance and bestow at least a fleeting sense of electedness on those he admitted.” But the luxuriousness came with an air of unparalleled snobbishness in the form of George C. Boldt, the man William hired to run the hotel, who is said to have torn up a customer’s bill when the customer had the impudence to question it, and banished him forever from the hotel. As another traveler wrote, “it’s an awful place, and my bill was the awfullest part of it.”

William’s new hotel would not have bothered Jack were it not for one little detail. The brownstone mansion that William demolished on Fifth Avenue was right next to another brownstone: the family home of Jack and, more important, his mother, the so-called “Mrs. Astor.” Not only did she have to suffer all the noise and dust from the construction works taking place next door, she soon found her mansion completely overshadowed by a massive hotel, its large, windowless back wall facing her house. She was forced to move out and build a new mansion elsewhere.

In retaliation, Jack in turn demolished his family’s brownstone, the one overshadowed by the Waldorf, and began constructing his own hotel in its place, one that would be even bigger and grander than the one next door. He called his new hotel the Astoria. Although developed in a similar style, the building was larger than its neighbor, with a conspicuously striking colonnade facade.

Realizing how foolish they must appear with their two hotels trying to compete with each other side by side, and, perhaps more important, realizing just how much profit they could make by merging them into one, the cousins decided to put aside their difference and combine their hotels. As the reluctant cousins shook their hands and their lawyers worked out the details of the deal, the Waldorf-Astoria was born (the original Waldorf-Astoria that is—the current Waldorf-Astoria on Park Avenue was built in 1931). The walls between the two buildings were knocked down, forming its famous Peacock Alley, “a three-hundred-foot-long, deep-carpeted, mirrored and amber marble corridor.”

The great department stores of the late nineteenth century “democratized luxury,” Emile Zola wrote, by offering ordinary people the opportunity to view and touch expensive goods of all sorts without obliging them to buy anything. In the same way, hotels such as the Waldorf-Astoria “brought exclusiveness to the masses” (said Oliver Hertford, a contemporary wit) and allowed the masses to see how the other (the upper) half lived. The Waldorf-Astoria made dining and lunching in public fashionable, brought society out into the open, and inspired an age of lavish entertainments, parties, balls, and dinners—grand occasions previously confined to private houses.

Unsatisfied by the truce, or perhaps wanting a monument that was wholly his own, William set off to build another hotel, one that would be even more exclusive than the Waldorf-Astoria.

Seventeen stories high, promoted as the tallest hotel structure in the world and the first to have telephones in every room and its own telephone exchange, the New Netherland commanded the main entrance to Central Park at Fifty-ninth Street and Fifth Avenue. In external style a gabled and turreted brown brick version of German Renaissance architecture, his new hotel was similar to the Waldorf, but it had a different ambience altogether, one of subdued but substantial elegance. In effect a marketplace and theater, the Waldorf-Astoria enclosed a world of glitter, wealth, and fashion bathed in an unremitting blaze of publicity. The New Netherland was aristocratic, reserved, and refined, more like a private club than a public facility.

William then built another hotel—Hotel Astor—one that was larger and more advanced than anything else at the time. Unlike the New Netherland, with its aura of a private club, Hotel Astor, located in Times Square, was a people’s hotel, a “less snooty, more egalitarian” version of the Waldorf-Astoria. The hotel came with an impressive assortment of technological innovations, including “air-conditioning; fire and smoke detectors in every room; electrically controlled fire doors; a ‘food escalator’ connecting the kitchen and banqueting rooms; an ice plant that produced 120 tons each day; an array of dynamos powering the elevators and the hotel’s fourteen thousand lights.” With its “fortresslike” walls, Hotel Astor was an enormous structure that housed more than “five hundred bedrooms served by twelve passenger elevators, a banqueting hall seating five hundred.” Its kitchen was said to be the largest in the world. Guest suites came in a medley of styles—art nouveau, Empire, Dutch Renaissance—and its public rooms seemed to offer a tour around the world: “an American Indian grill room; a Chinese tearoom; a Flemish smoking room; a Spanish lounging room; a Pompeian billiard room; a German ‘Hunt Room’ decorated with stag-horn light fixtures and continuous frieze showing scenes of the chase.” Almost immediately after the hotel opened its doors, its lobby turned into a kind of agora, a public meeting place.

Not to be outdone by his cousin, Jack, in his turn, built a structure that was one floor taller than William’s New Netherland. St. Regis, which opened its doors in 1904 at 2 East 55th Street, was a modern technological marvel. As a contemporary critic of architecture wrote, it was “probably the most complicated piece of mechanism which the invention and ingenuity of man have ever been called upon to devise. The only other modern mechanical contrivances which might be in the same class are a contemporary battleship and ocean-liner … The bowels and frame of such a building are in truth comparable only to the human body in the complexity and interdependence of the processes that go on within.” And, like the other Astor hotels, St. Regis was overflowing with luxury, offering such things as “a library of leather-bound books, an ‘Elizabethan’ tearoom hung with Flemish tapestries depicting incidents in the life of King Solomon, a sidewalk café, a skylight ballroom on the eighteenth floor, and a bronze-and-glass sentry box for the doorman.” Its enormous dining room was modeled on the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Shortly afterwards, in 1906, Jack built another hotel, in Times Square, called Hotel Knickerbocker. This was a slightly more restrained project, aimed at “out-of-town visitors of moderate means.”

The Astor cousins’ drive to build grand hotels was not motivated by profit. As Kaplan writes, “they could have made more money just by doing nothing but raking in rents, interest, and dividends from what they already owned. They had chosen hotels to be the stage for a family drama of pride, spite, rivalry, self-projection, and the love of grandeur and prominence.” If wealth was to be transformed into status, it had to be spent—or conspicuously consumed, as Veblen puts it—and it had to be spent on something both public and ostentatious. The grand hotel is, perhaps, the ultimate form of conspicuous consumption—a lavishly decorated and furnished house designed to be passed through, designed for an efficient turnover of visitors who get to experience its opulence for a moment before moving on and making space for others next in line. It is, in a sense, conspicuous consumption on a conveyor belt—the product of a fabricating mind coupled with a status hungry heart.

The trouble, however, is that by attaching your grand monument to a process of consumption, the monument itself becomes consumed. In The Last American, published in 1889, J. A. Mitchell imagines a remote future in which Persian explorers going through the ruins of New York stumble upon an upturned slab lying in the grass. The explorers examine the characters upon it “chiselled ten centuries ago.” “The inscription is Old English,” one of them said. “‘House’ signified a dwelling, but the word ‘Astor’ I know not. It was probably the name of a deity, and here was his temple.” Mitchell was off by nine centuries, for in 1926 the building was completely demolished, leaving no slab to inform the future explorers of the deity that once graced its halls.

Only two of the Astor cousins’ hotels remain: the forward-looking St. Regis and the Knickerbocker. Astor House, Hotel Astor, The New Netherland and the original Waldorf-Astoria have all been torn down at the beginning of the 20th century. Even the “fortress-thick” walls of Hotel Astor could not withstand the wrecking ball, though the workmen tasked with its demolition “said it was the most difficult job of its sort they had ever known.” The thing that made it profitable also sped up its demise. Could a non-commercial monument have fared better? If they had built a library, or a museum, or a church, would it still be standing today? Perhaps. Their great-grandfather, John Jacob Astor, did build a library in 1854, which was, incidentally, the one large public contribution he had ever made. It still stands there now over one and a half centuries later in Manhattan’s East Village, though now used as a theater.